In the tumultuous summer of 1950, the Korean Peninsula was engulfed in a brutal war. The North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) invaded South Korea on June 25th, swiftly pushing the ill-prepared South Korean forces and hastily deployed United Nations (UN) troops to a precarious defensive perimeter around the southeastern port city of Pusan. Facing desperate odds, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, Commander-in-Chief of the UN Command, conceived a daring and strategically brilliant plan: the amphibious landing at Inchon.

The Dire Straits of the Pusan Perimeter (July – August 1950)

By late July and August 1950, the UN forces were in a critical state. The NKPA, with Soviet-era tanks and artillery, held numerical superiority, pinning UN troops within the small Pusan Perimeter. Casualties mounted, supplies dwindled, and morale was strained. The North Koreans, confident from their rapid advance, believed UN forces were too weak to counterattack, expecting the Perimeter to collapse.

The NKPA’s objective was total victory: unify the peninsula under communist rule. They launched relentless assaults in the Battle of the Pusan Perimeter, contesting every inch of ground. Defenders fought desperately, relying on air support and naval gunfire to repel attacks. Despite operating on interior lines, UN forces were outnumbered and outgunned, leading to concerns in Washington D.C. that the Perimeter might not hold.

MacArthur’s Audacious Idea: A “Playing Dead” Strategy

General MacArthur, a veteran known for bold decisions, saw opportunity amidst despair. He recognized the NKPA’s overextended supply lines, stretching hundreds of miles south, and the relatively light defenses around Inchon, on Korea’s west coast, far behind enemy lines.

MacArthur’s strategy was to “play dead.” He allowed the North Korean advance to continue, seemingly confirming their belief that UN forces were solely focused on defending Pusan. This deception lured the NKPA deeper into South Korea, further stretching their logistics and diverting attention from the vulnerable west coast. This feigned weakness was crucial. The North Koreans, convinced of imminent victory, committed nearly all reserves to the Pusan front, leaving their rear exposed. MacArthur understood a conventional frontal assault from Pusan would be costly and risky. He sought a decisive blow from the rear to break the stalemate and reverse the war’s fortunes.

The Conception and Planning of Operation Chromite (Summer 1950)

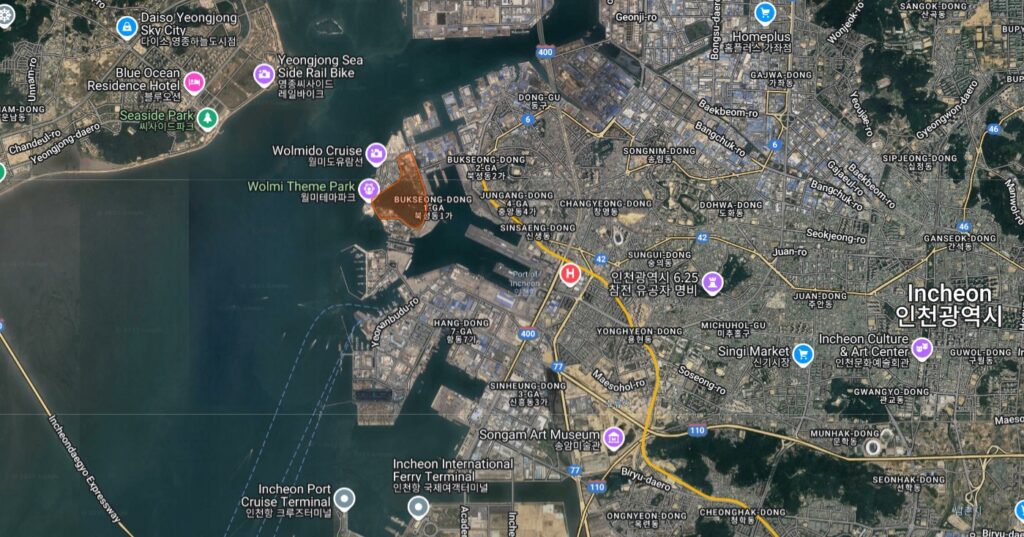

MacArthur faced significant skepticism from the Pentagon and his own staff due to Inchon’s formidable geographical challenges. The harbor had narrow, treacherous tidal flats, an extreme tidal range (up to 30 feet), restrictive channels, and a high seawall. Concerns also included strong currents and limited landing beaches. General J. Lawton Collins and Admiral Forrest Sherman flew to Tokyo to dissuade MacArthur, but he remained resolute. He famously argued that Inchon’s very difficulty made it strategically sound, as the enemy would least expect an attack there. His passionate argument ultimately swayed them.

Planning for Operation Chromite began in August 1950. Key figures included:

- General Douglas MacArthur: The driving force, championing the plan against opposition.

- Rear Admiral J.H. Doyle: Commander of the Amphibious Force, navigating Inchon’s challenging waters.

- Major General Edward M. Almond: Commander of X Corps (U.S. 1st Marine Division, U.S. Army 7th Infantry Division), leading the ground assault.

The multi-pronged assault plan included:

- Wolmi-do Island (Green Beach): A fortified island guarding the harbor. It was secured on September 15, 1950, neutralizing defenses for the main landing.

- Red Beach and Blue Beach: Main landing sites on Inchon docks and south, timed precisely for brief high-tide windows.

The Daring Landing at Inchon (September 15, 1950)

Against all odds, the Inchon landing was a resounding success. The initial assault on Wolmi-do by the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, was swift, securing the island with minimal UN casualties. This opened the way for the main force. Later that day, from the USS Mount McKinley, MacArthur watched as main UN forces landed at Inchon amidst challenging tidal conditions. The first waves hit Red Beach at 6:30 PM, scaling the seawall. Despite scattered resistance, surprise was overwhelming.

The North Koreans were caught completely off guard. They had focused forces on Pusan, leaving only a small, understrength garrison at Inchon. UN forces quickly overwhelmed defenders, securing the port and establishing a critical beachhead. The speed and scale of the landing disoriented the few North Korean units, preventing a coordinated counterattack.

Cutting Off the Enemy and the Tide Turns

Inchon’s strategic location was brilliant. By establishing a strong UN presence far behind NKPA lines, MacArthur effectively severed their supply routes and communications stretching from North Korea to Pusan. Isolated NKPA forces in the south now faced encirclement and destruction, cut off from reinforcements, ammunition, and food. This predicament was compounded by the NKPA committing nearly all combat-ready forces to the Pusan front, leaving their rear vulnerable.

Faced with this devastating turn of events, the North Korean offensive against the Pusan Perimeter collapsed. Many NKPA units found themselves trapped between advancing UN forces from Inchon and those breaking out of Pusan. UN forces within the Perimeter, now reinforced and morale boosted, launched a vigorous breakout northward. Simultaneously, X Corps, having secured Inchon, advanced southward towards Seoul and eastward to link up.

The Recapture of Seoul and the Shift in the War

The recapture of Seoul on September 28, 1950, just 13 days after Inchon, marked a decisive turning point. The battle for the South Korean capital was fierce, but UN forces prevailed. Inchon had not only saved UN forces from defeat but dramatically shifted the strategic initiative. The once invincible NKPA was now in full retreat, facing annihilation or capture. Tens of thousands of North Korean soldiers were killed or captured, and their logistical infrastructure shattered. UN forces, now on the offensive, rapidly advanced northward, pushing NKPA remnants back across the 38th Parallel. This bold maneuver transformed a defensive struggle into a victorious counteroffensive, fundamentally altering the conflict’s trajectory.

Historical Significance

MacArthur’s Inchon landing is widely regarded as one of military history’s most audacious and successful amphibious operations. It showcased the importance of strategic thinking, exploiting vulnerabilities, and taking calculated risks. Though controversial due to inherent dangers and initial opposition, its success is undeniable. It bought critical time, saved South Korea, and enabled the subsequent push northward. Lessons from Inchon about amphibious warfare and strategic surprise continue to be studied globally.

Sources

- “War Without End: The Korean War, 1950-1953” by Clayton K.S. Chun

- “The Korean War: A History” by Bruce Cumings

- “MacArthur’s War: Korea and the Undoing of an American Hero” by Stanley Weintraub

- “Inchon: The Inevitable Triumph” by Walter J. Boyne

- Official Histories of the Korean War by the U.S. Army Center of Military History

- Contemporary News Reports and Archives