The Spark of Chaos: March 4, 2011

The Libyan desert night was cold, the kind that bites through even the toughest resolve. On March 4, 2011, a Chinook helicopter sliced through the darkness, its blades a low thrum over the dunes near Benghazi. Inside, six elite SAS operatives from 22 SAS Regiment, call signs “Shadow One” to “Shadow Six,” sat shoulder-to-shoulder with two MI6 officers. Their mission: make contact with the ragtag rebels of the National Transitional Council (NTC) to forge an alliance against Muammar Gaddafi’s iron grip. Could these rebels, barely organized and deeply suspicious, become the key to toppling a dictator?

The team, led by a seasoned SAS captain known only as “Tomcat,” carried encrypted radios, maps, and C8 carbines concealed under civilian jackets. Their objective was simple but high-stakes: establish trust, gather intelligence, and lay the groundwork for NATO’s looming intervention. But as the chopper touched down, kicking up clouds of sand, things unraveled. Local farmers, mistaking the team for Gaddafi loyalists or foreign mercenaries, raised the alarm. Within hours, NTC rebels surrounded the SAS, weapons drawn, demanding answers.

What happens when the world’s most secretive soldiers are caught in the open?

The team was detained, their gear—night-vision goggles, laser designators, and a cache of explosives—scrutinized by wary rebels. After tense negotiations, brokered by a quick-thinking MI6 officer fluent in Arabic, the team was released on March 6 and evacuated aboard HMS Cumberland. The mission was a humiliating misstep, splashed across global headlines. But for the SAS, it was a lesson: Libya’s chaos demanded precision, stealth, and patience.

Would they adapt, or would the desert swallow their next move?

Into the Shadows: March 19, 2011

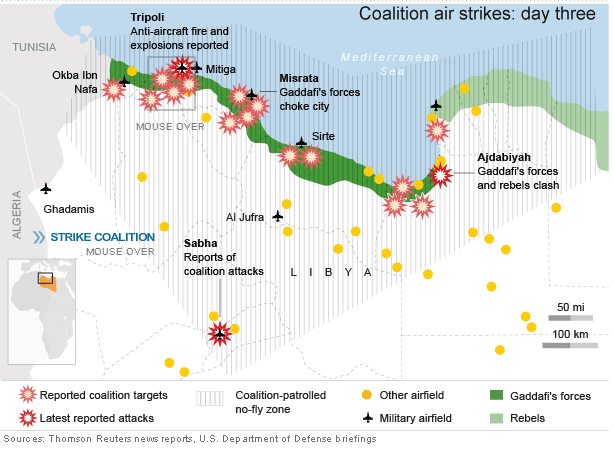

As NATO’s Operation Unified Protector launched on March 19, 2011, with airstrikes hammering Gaddafi’s air defenses, the SAS recalibrated. Over 250 operatives, split into small four-to-eight-man teams, fanned out across Libya’s sprawling deserts and war-torn cities. Their new orders: stay invisible, strike surgically, and turn the tide for the rebels.

How do you fight a war when you’re outnumbered, outgunned, and can’t be seen?

One such team, “Viper Squad,” led by Sergeant “Hawk,” a grizzled veteran with a knack for desert survival, operated near Misrata. On March 25, 2011, they set up a covert observation post (OP) in a shelled-out building overlooking a Gaddafi tank column. Using a portable RQ-20 Puma drone, Hawk’s team mapped the positions of T-72 tanks and relayed coordinates via encrypted satellite comms to NATO’s command center in Naples. At 3:17 a.m., an RAF Tornado screamed overhead, its laser-guided Paveway bombs obliterating three tanks in a fireball that lit the night.

Precision or luck? The SAS didn’t care—as long as it worked.

Viper Squad’s toolkit was a marvel of modern warfare: L115A3 sniper rifles for long-range eliminations, Javelin anti-tank missiles for armored threats, and lightweight laser designators to paint targets for NATO jets. Their modified Land Rovers, nicknamed “Pinkies” for their desert camo, bristled with .50 caliber machine guns and carried enough water and rations for two weeks of self-sufficiency.

Could they outlast Gaddafi’s loyalists in a game of cat and mouse?

Sabotage and Stealth: April-June 2011

By April, the SAS shifted gears to direct action. On April 12, 2011, a team codenamed “Spectre” infiltrated a Gaddafi supply depot near Zintan under cover of darkness. Led by Lieutenant “Ghost,” a wiry officer known for his cool-headedness, the four-man team crept past sentries, planting C4 charges on fuel trucks and ammo crates. At 2:43 a.m., the depot erupted in a chain of explosions, crippling Gaddafi’s supply line to the western front. The team vanished into the desert, leaving loyalists scrambling. How do you strike and disappear when every eye is watching?

Spectre’s success relied on meticulous planning. Before the raid, they spent days conducting close target reconnaissance (CTR), using night-vision optics to track guard rotations and SIGINT gear to intercept radio chatter. Their escape route, plotted via GPS, exploited dry riverbeds to avoid detection. The mission’s precision—zero casualties, maximum disruption—became a template for SAS operations across Libya.

Meanwhile, in Tripoli’s suburbs, SAS teams embedded with NTC rebels, teaching them to use captured RPGs and coordinate ambushes. On May 19, 2011, Hawk’s Viper Squad guided a rebel unit in a night assault on a loyalist checkpoint, using real-time drone feeds to outmaneuver Gaddafi’s forces. The rebels, initially disorganized, began to fight like a cohesive unit, thanks to the SAS’s crash course in small-unit tactics.

Could these unlikely allies turn the tide in a city on the brink?

The Tripoli Push: August 20-23, 2011

As summer scorched Libya, the rebels prepared for their boldest move: the capture of Tripoli. On August 20, 2011, SAS teams, including Viper Squad, moved into position around the capital. Their role was critical: mark targets for NATO airstrikes and guide rebel fighters through Tripoli’s labyrinthine streets. Could they navigate a city ready to explode?

Hawk’s team set up an OP on a rooftop overlooking Bab al-Azizia, Gaddafi’s fortress-like compound. Using a laser designator, they painted an anti-aircraft battery for a French Mirage jet, which obliterated it at 4:09 a.m. on August 21. The strike cleared the way for rebels to breach the compound’s outer defenses. Hawk, armed with an MP5 and night-vision goggles, led a small rebel unit through a sewage tunnel, avoiding loyalist snipers. By August 23, Tripoli fell, and Gaddafi fled.

Was this the endgame, or just another chapter in the SAS’s shadow war?

The Final Hunt: October 20, 2011

By October, Gaddafi was cornered in his hometown of Sirte. The SAS, now operating with Canada’s JTF2, intensified their hunt. On October 18, 2011, a team codenamed “Reaper” tracked a loyalist convoy via drone surveillance, suspecting Gaddafi was aboard. Reaper’s leader, Captain “Falcon,” a sniper with a reputation for uncanny accuracy, relayed coordinates to NATO. At 8:30 a.m. on October 20, a US Predator drone and a French Mirage struck the convoy, wounding Gaddafi. Rebels captured and killed him hours later.

Did the SAS’s precision tip the scales, or was it chaos that claimed the dictator?

Reaper’s mission showcased their relentless precision: days of drone surveillance, SIGINT intercepts pinpointing Gaddafi’s encrypted phone calls, and seamless coordination with NATO air assets. The team’s ability to operate undetected in Sirte’s warzone, despite heavy fighting, underscored their mastery of covert warfare.

The SAS Edge: Precision in Chaos

The SAS’s Libya campaign was a masterclass in special operations. Their small teams—never more than eight—used technology (drones, lasers, SIGINT) and training (CTR, sabotage, rebel coordination) to achieve outsized impact. Every mission, from the failed Benghazi landing to the Sirte endgame, was planned with surgical accuracy: routes mapped to the meter, targets struck within minutes, and escapes executed before dawn. How did they pull it off in a country tearing itself apart?

The answer lay in their adaptability. After the Benghazi fiasco, they refined their approach, blending into the desert and rebel ranks. They turned distrust into alliances, chaos into opportunity. By October 20, 2011, when Gaddafi’s death marked the war’s end, the SAS had left no trace—only results.

What other secrets lie buried in Libya’s sands, known only to the shadows who fought there?