The Nazi Nuclear Threat at Vemork

February 1942, Telemark, Norway

What if a single factory in Norway’s frozen wilds held the key to a Nazi atomic bomb? In the snow-covered valleys of Telemark, the Vemork hydroelectric plant produced heavy water, a rare substance critical for Germany’s nuclear ambitions. If the Nazis succeeded, the war could shift catastrophically. A small group of Norwegian skiers, armed with courage and explosives, prepared to risk everything to stop them. Could they outwit the German war machine in one of World War II’s most daring raids?

Allied Intelligence Targets Heavy Water

By 1942, the Third Reich’s nuclear program was a growing concern for the Allies. Intelligence from Norwegian scientist Leif Tronstad confirmed that the Norsk Hydro plant at Vemork, near Rjukan, was producing deuterium oxide—heavy water—essential for nuclear reactors. Under Nazi occupation, the plant’s output fueled Germany’s race for an atomic bomb. The Allies, aware of the stakes, planned to sabotage the facility. Vemork, perched on a cliff above a 600-foot gorge, was a fortress guarded by German soldiers and surrounded by Norway’s brutal winter.

Operation Freshman’s Tragic Failure

The first attempt, Operation Freshman, launched on November 19, 1942, ended in disaster. British commandos and Norwegian resistance fighters aimed to glide onto the Hardangervidda plateau, a snow-swept wilderness near Vemork. Two gliders, towed by Halifax bombers, departed from Scotland, but treacherous weather struck. One glider crashed into a mountainside, killing seven men. The second crash-landed, and the Gestapo captured the survivors, executing all 14 under Hitler’s “Commando Order.” Declassified SOE reports document the failure, which alerted the Nazis, tightening Vemork’s security.

Joachim Rønneberg Leads Operation Gunnerside

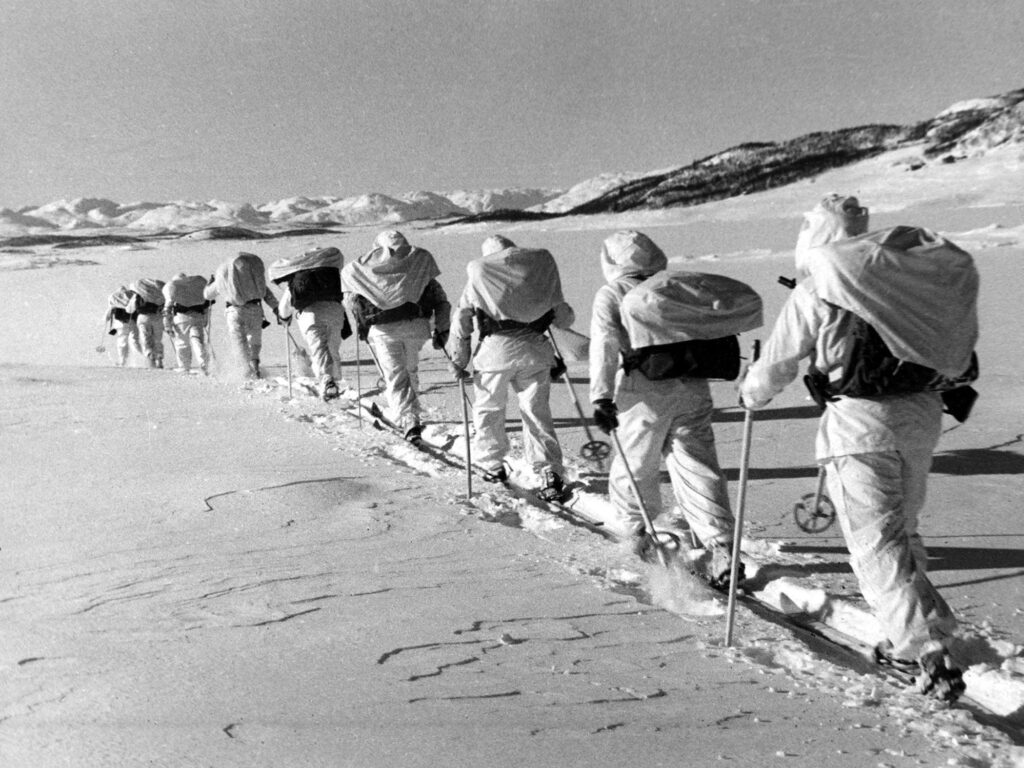

Undeterred, the Allies turned to Joachim Rønneberg, a 23-year-old Norwegian resistance fighter trained by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE). In January 1943, he led Operation Gunnerside, a daring mission to destroy Vemork’s heavy water cells. The plan: parachute onto the Hardangervidda, join the advance “Grouse” team, ski 30 miles through blizzards, scale a cliff, and infiltrate the fortified plant. Rønneberg’s team—Knut Haukelid, Arne Kjelstrup, Jens-Anton Poulsson, and others—knew the terrain and skied with precision, but German patrols and extreme cold posed constant threats.

Surviving the Hardangervidda’s Harsh Winter

On February 16, 1943, Rønneberg’s team parachuted into Norway. High winds scattered their supplies, landing them miles from their target. For days, they battled minus-20-degree temperatures, digging snow caves to survive. “We were frozen to the bone, but we had no choice,” Rønneberg recalled in a 1987 Guardian interview. They rendezvoused with the Grouse team, led by Poulsson, who had endured months in hiding, living off reindeer moss. Using smuggled blueprints from Leif Tronstad, now in London, the saboteurs planned their assault on Vemork.

Climbing the Cliff to Vemork

On February 27, 1943, under a moonless sky, the team skied to the gorge below Vemork. The guarded bridge was impassable, so they chose a near-impossible route: a 600-foot climb up a sheer, ice-covered cliff. Clutching roots and rocks, they ascended in silence. “One slip, and we’d be dead,” Knut Haukelid wrote in Skis Against the Atom. By midnight, they reached the top, undetected. Vemork’s lights pierced the darkness, its heavy water cells humming inside, fueling Hitler’s nuclear dream.

Sabotaging the Heavy Water Cells

The team split up. Rønneberg and Fredrik Kayser crawled through a cable duct into Vemork’s basement, where the 18 heavy water cells were stored. Arne Kjelstrup and others stood guard, ready for alarms. A Norwegian worker, startled but loyal to the resistance, guided them. Rønneberg placed small explosive charges on the cells, using short fuses for a swift escape. At 1:24 a.m. on February 28, 1943, a muffled blast shook the plant. Five hundred kilograms of heavy water spilled, and the cells were destroyed. The team skied away as alarms sounded, escaping without a shot fired.

Allied Bombings and Operation Swallow

The sabotage crippled Vemork, but the Nazis repaired it by late 1943. On November 16, 1943, American B-17 bombers attacked, damaging the plant but killing 22 Norwegian civilians, a tragedy recorded in Norwegian archives. When Germany tried to ship the remaining heavy water to Berlin in February 1944, Knut Haukelid led Operation Swallow, sinking the ferry Hydro in Lake Tinnsjø. The attack destroyed the cargo but killed 14 civilians, a heavy cost for the resistance. These actions ensured the Nazis could not rebuild their nuclear program.

Legacy of the Norwegian Resistance

The Vemork operations delayed Germany’s nuclear ambitions, likely preventing an atomic bomb before the war’s end in 1945. Historian John S. Craig, in The Oxford Companion to World War II, credits the sabotage with hobbling the Reich’s nuclear efforts. Rønneberg and his team, after escaping to Sweden and Britain, continued resistance work. Rønneberg, who died in 2018, remained modest, saying in a 2015 BBC interview, “We just did our job.” Their story, celebrated in The Real Heroes of Telemark by Ray Mears and the 1965 film The Heroes of Telemark, showcases unparalleled bravery.

A Victory Against the Odds

The Norwegian saboteurs, through sacrifice and skill, changed history. From the frozen cliffs of Telemark to the sunken ferry in Lake Tinnsjø, their actions ensured the Nazi atomic bomb remained a dream. In the face of brutal winters, German patrols, and impossible odds, a few skiers proved that courage could shift the course of a war.

Sources:

- Declassified SOE reports, UK National Archives.

- Haukelid, Knut. Skis Against the Atom (1954).

- Craig, John S. The Oxford Companion to World War II (2001).

- Interviews with Joachim Rønneberg, The Guardian (1987) and BBC (2015).

- Norwegian Resistance Museum records, Oslo.

- Watch The Heavy Water War (English subtitled) | Prime Video