The Bosnian War (1992-1995) left a brutal legacy of ethnic cleansing, mass atrocities, and a desperate need for justice. As the fighting subsided, a new, covert battle began – the hunt for the individuals responsible for these heinous crimes. At the forefront of this silent war were elite special forces, notably the British Special Air Service (SAS), who undertook highly dangerous missions to apprehend indicted war criminals for trial at The Hague.

The Aftermath of War: A Landscape of Impunity

The Bosnian War, marked by widespread violence against civilians, including the genocide in Srebrenica in July 1995, resulted in indictments by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), established on May 25, 1993. However, in the immediate aftermath of the Dayton Accords (signed December 1995), NATO forces (initially IFOR, then SFOR) on the ground were largely hesitant to make arrests, fearing potential destabilization and a resurgence of conflict. This policy, often termed “mission creep,” created a climate where many high-profile war criminals, including political and military leaders, remained at large, often protected by local networks and even elements within the police and military structures of the newly formed entities.

The Shift: From Reluctance to Active Pursuit

The initial reluctance of peacekeepers to engage in arrests began to change around mid-1997. Growing international pressure and the ICTY’s persistent calls for cooperation, coupled with the realization that justice was integral to lasting peace, led to a more assertive approach. This shift paved the way for special forces units to become actively involved.

The SAS Enters the Fray: Operation Tango and Beyond

While the full extent of SAS operations in Bosnia remains largely classified, accounts and declassified information confirm their crucial role in apprehending war criminals. Post-war, the SAS returned to Bosnia for a series of missions focused on these arrests. One such mission was notably codenamed Operation Tango.

The SAS, alongside other special forces units from countries like the United States (Delta Force), France, Germany, and the Netherlands, participated in a broader, joint effort known as Operation Amber Star. This initiative, assembled at Patch Barracks in Stuttgart, Germany, aimed to provide the ICTY with the “teeth” it needed. While a multinational effort, individual special forces often worked separately on specific targets, leveraging their unique capabilities and intelligence.

Tactics of the Covert Hunt:

The methods employed by the SAS and other special forces were sophisticated and highly clandestine, often involving:

- Sealed Indictments: A critical innovation by the ICTY, these indictments meant that suspects were unaware they were wanted until the moment of their capture. This prevented them from going deeper into hiding or organizing resistance.

- Precision Raids: Operations were meticulously planned, often involving rapid deployment by helicopter or unmarked vehicles, targeting suspects in their homes, businesses, or even on the move. Surprise was paramount.

- “Snatch” Operations: These involved quick, decisive arrests designed to minimize casualties for both operatives and bystanders. The objective was to seize the individual, secure them, and extract them rapidly to a safe location before transporting them to The Hague.

- Intelligence Gathering: Extensive surveillance, human intelligence, and technical intelligence were crucial to pinpointing the whereabouts of fugitives. This often involved living covertly in Bosnia, blending into local communities or operating from hidden observation posts.

- Border Crossings and Extractions: Many war criminals sought refuge across borders, particularly in Serbia. SAS and other special forces sometimes conducted operations that involved covertly crossing borders, apprehending targets, and extracting them back into NATO-controlled territory in Bosnia for formal arrest and transfer.

Key Figures and Notable Apprehensions (with SAS involvement or in the broader context):

While direct attribution to the SAS for every arrest is difficult due to secrecy, their presence was a significant deterrent and a major factor in the capture of many individuals:

- Stevan Todorović (Police Chief of Bosanski Šamac): Captured by the SAS in September 1998 in a daring operation that extended into Serbia itself. A four-man SAS team, fluent in Serb, stormed his cabin, bound and gagged him, drove him to the Drina River, and then transported him by inflatable boat across the border into Bosnia, where he was loaded onto a helicopter for transfer to Tuzla and then The Hague. Todorović was later sentenced to 10 years for crimes including torture and beatings. This operation highlighted the SAS’s willingness to operate in hostile territory.

- Anto Furundžija (Bosnian Croat Commander): Apprehended by the SAS in December 1998. He was subsequently sentenced to 10 years for torture. This case, and others like it, demonstrated that the hunt was not solely focused on Serb indictees, but on perpetrators from all sides of the conflict.

- Vlatko Kupreškić (Bosnian Croat Soldier): Captured by the SAS in 1997 as part of Operation Tango. While initially sentenced to six years for involvement in the Ahmići massacre, his conviction was later overturned on appeal due to insufficient evidence. This case underscores the careful legal process that followed the captures, even for high-value targets.

- Stanislav Galić (Bosnian Serb General): Sentenced to life imprisonment by the ICTY for his role in the siege of Sarajevo, which involved systematic shelling and sniping of civilians. While the details of his specific apprehension are less publicly known, his capture was part of the intensified efforts during this period.

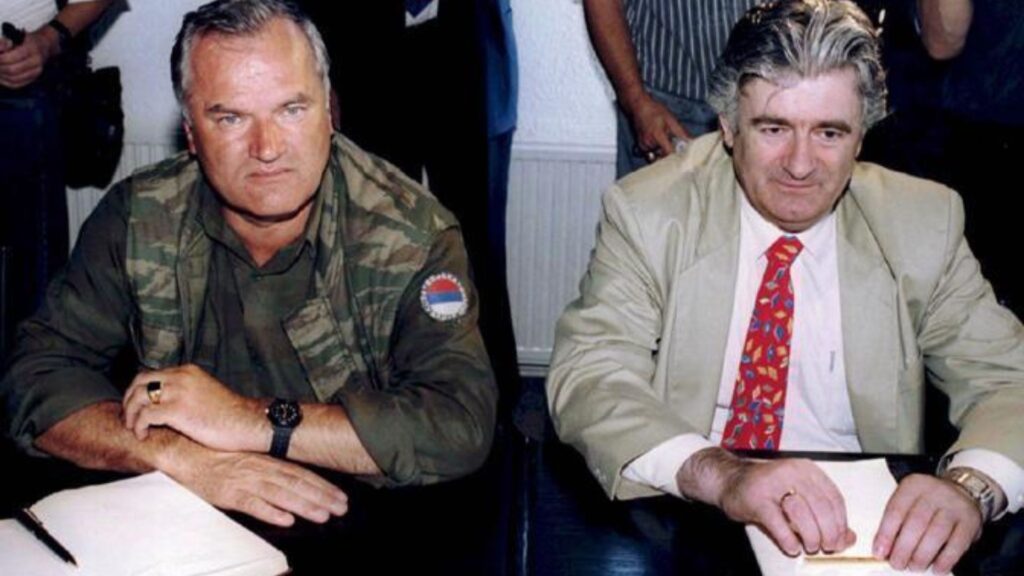

The high-profile figures of Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić remained at large for many years, often protected. While US Delta Force led many of the specific attempts to capture Karadžić, the overall “manhunt” involved a broad network and shared intelligence, with the SAS contributing significantly to the wider environment of pressure and successful arrests that eventually led to their apprehension in Serbia in 2008 and 2011 respectively.

Challenges and Controversies:

The operations were not without significant challenges:

- Risk to Operatives: The targets were often armed and had loyalists, making every arrest a high-risk endeavor. There were instances of resistance, and operatives faced the constant threat of ambush or reprisal.

- Legal Complexities: The legality of military forces arresting civilians was a complex issue, requiring careful coordination with the ICTY and adherence to international humanitarian law. A “complex minuet” was often arranged where SFOR troops would detain suspects at the request of the ICTY, until tribunal officials could formally make the arrest.

- Political Sensitivities: Arrests in a still-fragile post-conflict environment carried the risk of reigniting tensions or causing a backlash from local populations or political factions.

- Intelligence Leaks: There were instances where intelligence on planned operations was believed to have been leaked, allowing targets to escape.

The Enduring Legacy:

The efforts of the SAS and other special forces in Bosnia were pivotal in demonstrating that impunity for war crimes would not be tolerated. Their secret missions, often carried out with remarkable daring and precision, contributed directly to the eventual apprehension of all 161 individuals indicted by the ICTY. This “butcher’s trail,” as described by author Julian Borger, not only delivered justice to countless victims but also established crucial precedents for international criminal justice, proving that even the most powerful individuals could be held accountable for their actions. The experience gained in Bosnia also profoundly influenced future special operations and intelligence gathering techniques, particularly in the post-9/11 era.

Sources (expanded and re-emphasized):

- International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY): Official records, case files, and press releases. (e.g., www.icty.org) – Essential for understanding the legal framework and outcomes.

- “The Butcher’s Trail: How the Search for Balkan War Criminals Became the World’s Most Successful Manhunt” by Julian Borger (2016): A highly authoritative book drawing on extensive research, interviews, and declassified documents, detailing the manhunt efforts, including the role of special forces. – Crucial for operational details and context.

- “Operation Amber Star” Wikipedia / International Bar Association Articles: Provide overviews of the multinational effort and the shift in policy regarding arrests. – Good for collaborative context.

- “Special Air Service (SAS) – BOSNIA OPERATIONS” Elite UK Forces: Offers specific information on SAS activities in Bosnia and mentions “Operation Tango.” (https://www.eliteukforces.info/special-air-service/history/bosnia/) – Directly relevant to SAS actions.

- “Good and bad war criminals – Declassified UK”: Contains specific details on SAS captures like Stevan Todorović and Vlatko Kupreškić, including operational descriptions. (https://www.declassifieduk.org/good-and-bad-war-criminals/) – Provides concrete examples of SAS arrests.

- Human Rights Watch Reports and Analysis: Documents like “The Failure to Arrest Radovan Karadzic” (2004) shed light on the challenges and various efforts to apprehend high-value targets. – Offers insights into the difficulties and broader political landscape.

- Academic and Policy Papers on ICTY Enforcement: Numerous scholarly articles and reports discuss the evolution of ICTY’s enforcement mechanisms and the role of military forces.